The discovery of antibiotics marked a historic milestone in the history of medicine. Antibiotics are molecules that kill the growth of bacteria and have led to saving countless lives. As far back as 2500 BCE the Egyptians used moldy bread and plant extractions to treat infection wounds, a practice also used in ancient Greece and China. The remedies were based on empirical observation rather than an understanding of the underlying biological mechanics. We sometimes forget the concept of a microorganism as an agent of disease was only developed in the 19th century by Louis Pasteur.

The Dawn of Antibiotics: Alexander Flemming’s Discovery of Penicillin

The discovery of antibiotics began in 1928 with Alexander Fleming’s accidentally discovery of penicillin. Flemming was Scottish bacteriologist working at St. Mary’s Hospital in London. He was experimenting with the Staphylococcus bacteria, a common bacterium responsible for infections such as boils, sore throats, and abscesses. In the late summer Flemming took a two-week vacation, but he left his lab with unwashed petri dishes. When he returned, he noticed that the petri dishes had been contaminated by a bluish green mold, and around this mold was a clear zone where the bacteria had been eliminated.

The mold belonged to the genus of fungi called Penicillium. Flemming became intrigued by what he saw and began isolating and experimenting with the mold. He discovered that through a chemical substance the mold secreted, it could kill or inhibit a wide range of harmful bacteria. Furthermore, it left human cells untouched, suggesting that it could be used for safe treatment in the human body. Flemming named the substance Penicillin, after the mold.

In 1929 he published his findings in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, noting that penicillin was effective against many disease-causing bacteria like streptococcus and meningococcus. However, the substance was unstable and difficult to purify and for nearly a decade the discovery remained largely overlooked by the broader scientific community.

The Oxford Team

Despite this groundbreaking observation, penicillin remained largely ignored by scientists for over a decade. In the late 1930s Howard Florey, an Australian pathologist, and Ernst Boris Chain, a German biochemist, were working at Oxford University. They rediscovered Flemming’s paper and quickly recognized its significance as a naturally occurring antibacterial substance. They faced several challenges including how to grow enough mold, how to extract and purify the ingredient, and proving their ideas could work. An Oxford team was put together, led by Florey, Chain, and Norman Heatley, to overcome these difficult challenges.

The first human trial came in 1941 on a policeman dying of horrific infections. The officer made an impressive recovery; however, supplies ran out and he died a few days later. Subsequent trials on wounded soldiers proved unequivocally that penicillin worked miracles where all else failed. World War Two provided an urgent need to develop penicillin as a treatment for soldiers, however British manufacturing was already under heavy strain due to the war. Later that year Florey and Heatley traveled to the United Stats to enlist American pharmaceutical companies and the US government’s support. Within two years, penicillin was being manufactured in quantities sufficient for military use.

The Antibiotic Boom

Penicillin’s success causes a global sensation and the race to discover new antibiotics was on. The post-war age saw an explosion of antibiotic discoveries. Pharmaceutical companies quickly isolated antibiotics from soil microbes, an area that proved to be a treasure trove of new antimicrobial compounds. These new drugs continued to transform medicine by making surgery safer, increasing infant mortality, and assisting in public health. Optimism was sky high in the 1960s that antibiotics could eliminate or reduce many infectious diseases. Their use eventually extended beyond medicine and into agriculture where they were used in animal livestock. However, there were early warnings about their limitations.

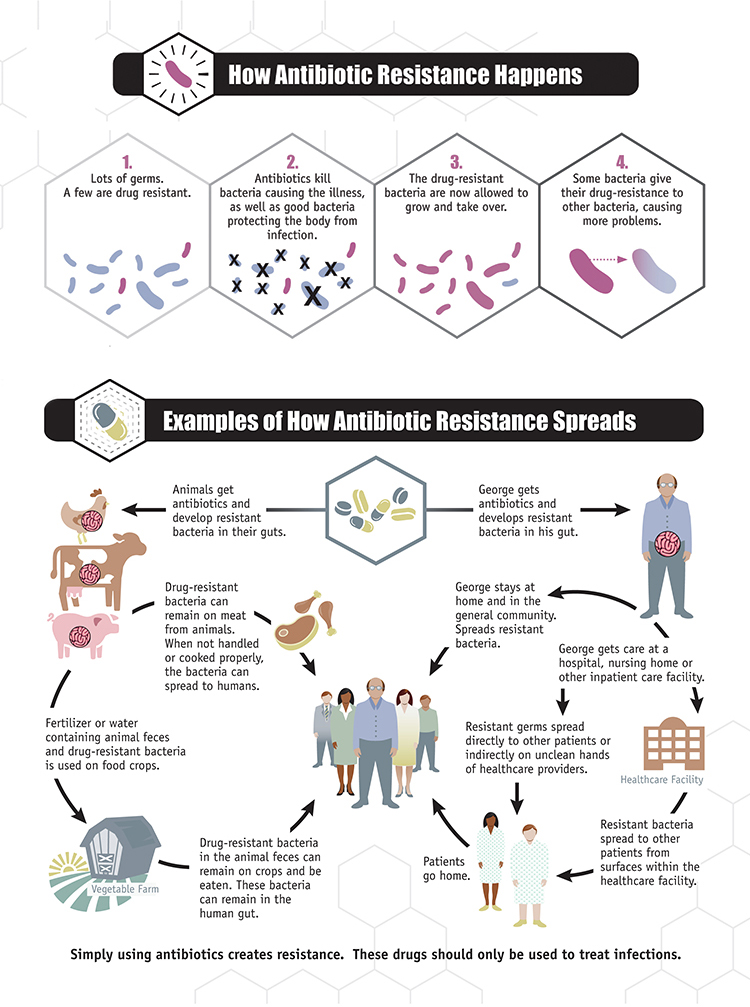

As early as 1945 Flemming cautioned in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech that bacteria could develop resistance to penicillin if used improperly. This proved to be true. Bacteria can and regularly does evolve resistance to antibiotics, by means of producing enzymes that degrade the drug or alter their cellular targets. Since they reproduce rapidly, going through several generations per day, it allows for a high mutation rate in a short amount of time. In a bacteria population most of the bacteria is low resistance to the antibiotic, but a few may be high resistance. The high resistance bacteria survive and reproduce, over time eventually taking over the population. What began as a population with little to no resistance becomes a population fully resistant to the antibiotic, and a new drug is needed to kill the new resistant bacteria. Overuse in medicine and agriculture accelerated resistance, exposing a critical flaw in the discovery of antibiotics: bacteria adapt faster than new drugs can be developed. Despite this challenge the discovery of antibiotics remains one of humanity’s greatest medical achievements, but its future depends on balancing innovation with responsibility.

Continue reading more about the exciting history of science!