The Germ Theory of Disease seems like common knowledge to just about everybody today, but this has not always been the case. Throughout most of history the causes of disease, the breakdown of the normal functioning of the human body – have been a mystery. This is not to say that a lack of ideas have existed.

A Brief History of Disease Theory

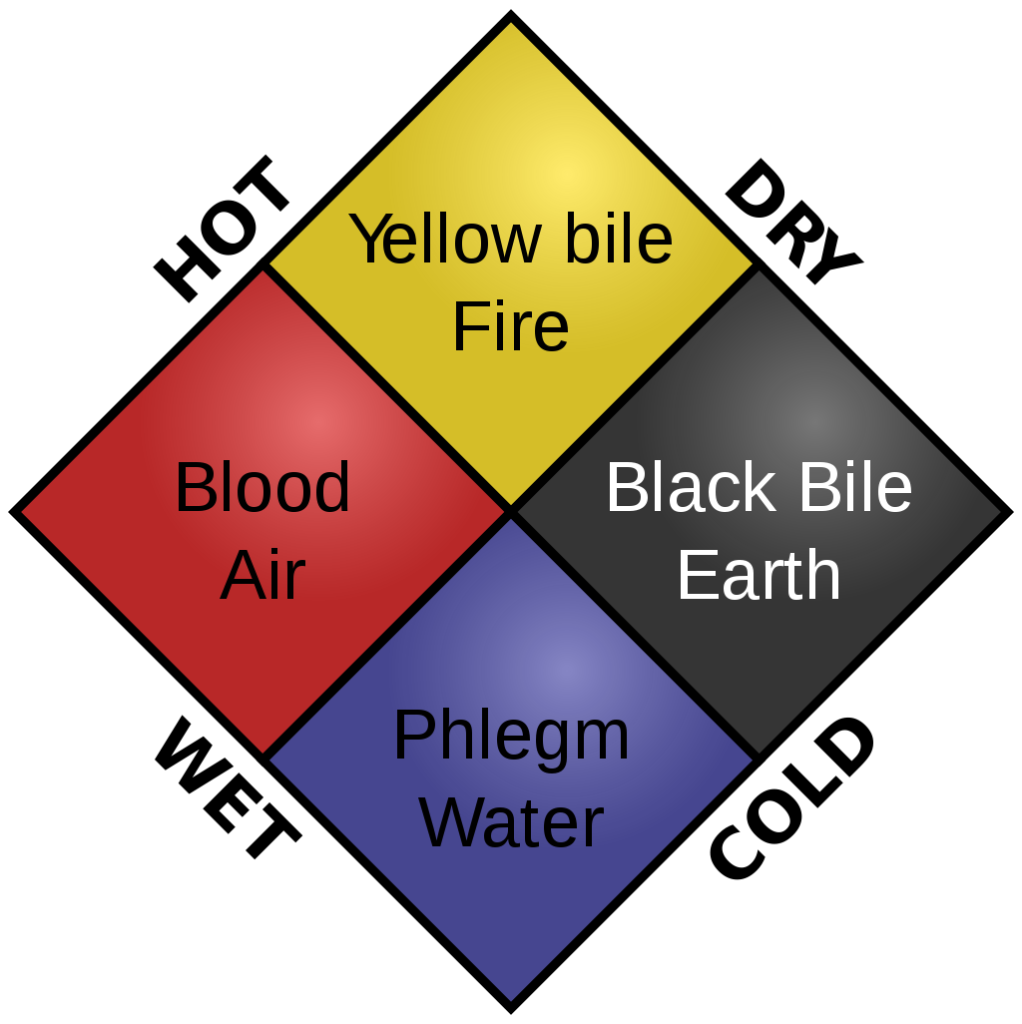

Early medical practices were awash in trial and error methods and a mix of science and superstition. One popular belief developed by the ancient Greeks and believed throughout the Middle Ages was known as humorism. Humorism states that the body contained four humors which were linked to the four major bodily fluids plus the four elements. An imbalance in humors was believed to cause disease. Cures revolved around restoring this balance.

(Credit: Tom Lemmens)

Religious and supernatural forces were also strongly believed to be tied to disease. Divine retribution may cause individual sickness or a demonic force would cause epidemics. However by the time of the Industrial Revolution the leading theory on disease was that bad air or “miasma” was believed to spread contagious diseases. This miasma would emit from rotting, dead organic matter to cause plagues, cholera, and various other diseases. People were instructed to avoid things such as decaying vegetation, corpses, and manure.

The invention of the microscope altered the landscape of medical science. Bacteria and viruses were discovered which led to a speculation of a germ theory of disease for centuries. In the mid-19th century The Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis noticed that Puerperal Fever could be drastically reduced simply by washing hands. Various publications reported that the mortality rate could be reduced to around 2% from the mid-20s. Curiously, these were completely ignored by the medical community. It is for this we get the metaphor Semmelweis reflex – the tendency to reject new knowledge because it contradicts established norms.

The Triumph of the Germ Theory of Disease

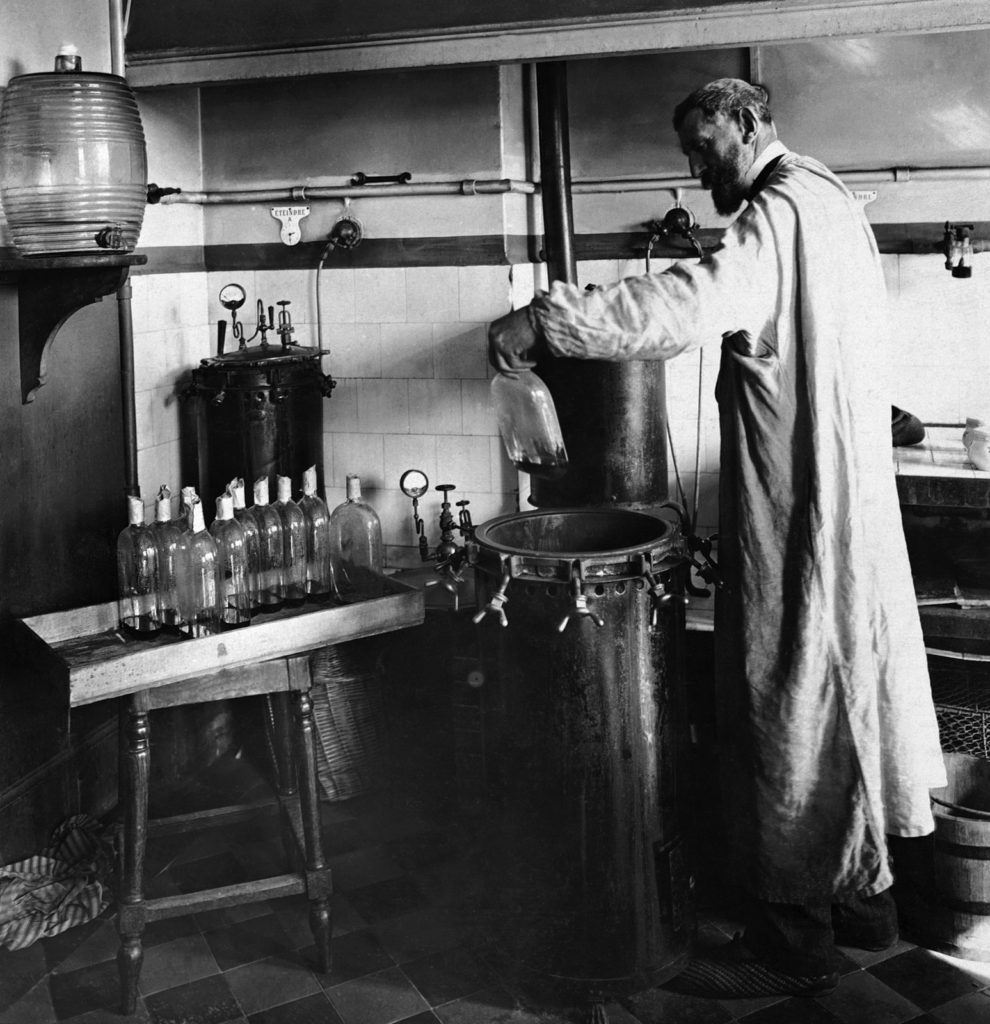

Beginning in the 1860s, the work of Louis Pasteur finally proved the Germ Theory of Disease. Pasteur first began to study the validity of spontaneous generation, the popular idea that living things spontaneously emerge from nonliving matter. He conducted several clever experiments showing that microorganisms cause fermentation. In one experiment he showed that fermentation would not take place in a solution sterilized by heat. He correctly attributed this result to the absence of living microorganisms in the sterilized solution. Through a variety of experiments in fermentation he was able to prove that specific microbes can bring about specific chemical changes.

Having gained some notoriety for his work on fermentation, in 1865 the French government asked Pasteur to study two diseases of silkworms that were devastating the French silk industry. He accepted the task, discovered again that microorganisms were the culprits, and saved the French silk industry. These experiments, along with his other work, proved that all living things must have parents.

(Credit: U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases)

A decade later Pasteur began to study anthrax. His work with anthrax and anthrax immunization proved to everyone once and for all the validity of the Germ Theory of Disease. In 1881 at a farm southeast of Paris, Pasteur conducted a public experiment to demonstrate his anthrax vaccine. He inoculated twenty-five sheep with weakened anthrax microbes. Two weeks later he injected those sheep and others with active anthrax. All twenty-five inoculated sheep survived, the rest all perished.

Along with Pasteur, Robert Koch is also recognized as having contributed to placing the Germ Theory on sound, scientific footing. He developed four basic criteria known as the Koch postulates that establish a cause and effect relationship between a microbe and a disease. It should be noted that viruses were later identified and cannot be cultured, so his postulates do not apply to them. Koch’s postulates are:

- The microbe must be found in the diseased animal, but not the healthy animal

- The microbe must be isolated in the diseased animal and grown in a pure culture

- When the cultured microbe is introduced to a healthy animal, the animal develops the disease

- The microbe must be re-isolated from the experimentally infected animal

An Immediate Impact to Health

The Germ Theory of Disease allowed us to discover exactly what cause certain diseases. Once the method was accepted and understood it quickly led to the identification of many specific, disease-causing microorganisms. This led to vaccinations and cures to many of the diseases. Also steps could be taken to prevent diseases too. Personal and hospital hygiene was improved with the aim at reducing the transfer of microbes from one source to another. As a result, life expectancy quickly began to rise at a rate unseen in human history. This is the power of science.

Continue reading more about the exciting history of science!